Western Victoria Quarter Part 3: Vehicle Prioritisation and Pedestrian Design Failures

Cars, Cars, Cars

Victoria Quarter suffers from a focus on wide roads and plentiful car parking. The image below highlights this prioritisation and land use by overlaying areas committed solely to the storage of cars (not including the space allocated to movements within the road itself!):

- Blue represents surface level parking or car parking buildings and associated driveways

- Green represents on street parking

- Red lines represent street frontage dedicated to cars (driveways, angle parking)

This prioritisation of car movements and parking results in some fairly negative impacts for the area:

- High vehicle speeds

- Driving encouraged to and within Victoria Quarter

- Inadequate, non-compliant footpaths which are generally obstructed by cars (legally and illegally)

- Difficulty for pedestrians to cross any street, especially children

- Many roads are impossible to cross in a wheelchair or with a pram

What does this glorified parking-lot-masquerading-as-a-Victoria-Quarter look like?

Wide roads…

…filled with cars…

…with footpaths always at risk…

… and aggressive on-street parking allocations that push aside any doubt that this is a place with any consideration for pedestrians

(How many people would blame the bicycle for being in the way of the crossing here?)

On foot

As a result of this car dominance, there are many, many areas where Victoria Quarter falls well short of the standards set in the NZTA Pedestrian Planning Guide (NZTAPPG) and Auckland Transport Code of Practice (ATCOP). Very few footpaths in the area could be considered ‘adequate’, let alone ‘good’ and it is possible to quantify all the ways that they fail by referencing these two standards.

Of course, applying new standards to existing areas will often result in impossible situations, but many are only impossible if the assumption that ample parking and extensive vehicle access are the primary requirement for the area. As mentioned a few times now - these road geometries predate motor vehicles and the roadway was not an especially dangerous place for pedestrians in ~1900 when they were laid out. The roads are as wide as they are now purely because they could be, not because anyone designed them for some specific traffic flow or parking parameters.

In each case I’ll take a standard, give a brief point about where we’re failing, give a reference giving quantifiable reasons why it fails and then some photos.

Footpath Widths (NZTAPPG 14.2.2, ATCOP 12.4)

Provision for parking and traffic lanes has eaten away at footpath widths throughout Victoria Quarter.

All new and improved developments should comply with the above widths. Where footpaths have not been provided to a suitable standard in the past, RCAs should develop works programmes to bring them up to a suitable standard.

NZTAPPG and ATCOP seem fairly aligned here:

NZTAPPG Table 14.3

ATCOP Table 32

When there appears to be not enough space available to install the appropriate footpath width, the step-by-step process in figure 14.2 should be used:

This seems pretty cut and dried, no?

NZTAPPG Figure 14.2

So many examples….

Passing Places (NZTAPPG 14.2.3)

Existing footpaths are so narrow as to be difficult to navigate in single file on foot and impossible to navigate by wheelchair, never mind two wheel chair users attempting to pass each other.

Where through route width is constrained to less than 1.5 metres wide, passing places should be provided – but only where it is not possible to widen the footpath over a longer distance, and never as a low-cost alternative to a full-width footpath. The advantages of passing places are:

- two wheelchairs can pass each other

- walking pedestrians can pass stationary pedestrians, such as those waiting to use a crossing or waiting for public transport.

How about this one?

Gradient & Crossfall (NZTAPPG 14.4, ATCOP 12.5, 12.6)

Driveway implementation throughout the area have created areas with unsuitable and, in some cases, dangerous gradients and crossfalls – even those of able body will struggle.

Crossfall is the slope of the footpath at right angles to the direction of travel. Some crossfall is required for drainage, but excessive crossfall in the through route requires people using wheelchairs and walking frames to use extra energy to resist the sideways forces. As the crossfall is invariably towards the road where footpaths are in the road reserve, anyone losing their balance is directed towards motorised traffic

Wheeeee

Driveways (NZTAPPG 14.11)

There are a large number of driveway entrances making up large portions of the footpaths. Very few have been designed to meet standards and most provide extreme, awkward gradients and crossfall to pedestrians, with no consideration for visibility or reducing obstructions.

Driveways should have a level landing at the top (similar to a kerb ramp), and be at least 1.2 m wide across the through path. The crossfall should be less than two percent, with the gradient differing from the adjacent through path by less than two percent. To achieve this, the sloped part of the driveway should be within the street furniture zone and/ or the adjacent private property. It may be necessary to lower the footpath

and

Footpaths on either side of the driveway should be kept clear of all obstructions. A five metre by two metre ‘visibility splay’ should be installed in areas with high pedestrian flows and more than 200 expected daily vehicle access manoeuvres

Not so great - the footpaths are so narrow that you’re forced to walk centimeters from corners where cars will be reversing out, with no margin for error.

The narrowness also forces driveways to slope across the footpath to reach the road, and as you’ve seen at the start of this post, there are a lot of driveways, meaning that the footpath doesn’t stand a chance.

Crossing Site Distance (NZTAPPG 15.3)

Many footpaths, such as those on Adelaide Street, have been cut back so far that buildings exist almost right up to the kerb. This, mixed with parking allocated right up to intersections, massively reduces visibility for pedestrians and drivers. The occurrence of steep hills and blind rises throughout the area exacerbates these issues.

At most crossing points pedestrians need to choose gaps in the traffic stream to cross safely, so they must be able to see the approaching traffic in good time. This distance, known as the ‘crossing sight distance’, is a critical element in ensuring pedestrians can cross the road safely

and

Drivers should be able to see all crossings easily so they can adjust their speed and be aware of the potential for pedestrians to step into the roadway. They should be able to see the crossing over at least the appropriate ‘approach sight distance’ although an extra safety factor is recommended.

This matters, a lot, when parking is permitted right up until the intersections:

Kerb crossing (NZTAPPG 15.6)/Pram Crossings (ATCOP 12.8)

A large number of intersections provide absolutely no kerb treatments, or treatments that are inadequate or crumbling.

Kerb crossings are an integral part of every crossing facility, whether mid-block or at intersections. Kerb crossings are of two types, kerb ramps and blended crossings

When designing kerb ramps, it is important to ensure that:

- if there is a kerb ramp on one side of the roadway, there is also one on the other to prevent pedestrians being ‘stranded’ on the roadway itself

- there are no low points in the gutter where water can collect

- if installed at a pedestrian crossing point, the whole kerb ramp is contained within the crossing markings Every kerb ramp comprises:

- the ramp, which is the area pedestrians cross to change their grade

- the top landing, which is where pedestrians move between the ramp and the footpath

- the approach, which is the section of footpath next to the top landing

- the gutter, which is the drainage trough at the roadway edge

…

Many kerb ramps also have flared sides, which are sloping areas next to the ramp, to prevent pedestrians tripping on the ramp edges. Some ramps also have a bottom landing. Return kerbs can be used instead if the kerb ramp is carefully located within the street furniture zone or at a kerb extension.

…

The various elements of kerb ramps can be combined in a number of ways.

…

Kerb ramps create particular problems for the vision impaired. This is because they often use the kerb face as a tactile cue for the footpath edge and kerb ramps can increase the risk of their inadvertently walking out into the roadway. To avoid this, all kerb ramps should incorporate appropriate tactile ground surface indicators.

…

Pram crossings must be provided at each kerb line at all intersections and also be provided at other locations to suit the logical and safe movement of pedestrians. Particularly on free left turns and where there is a large radius kerb line, pram crossings must be located to ensure adequate sight distances for both the pedestrian and the vehicle road user. Pram crossings should generally be placed to provide the minimum crossing distance, but also in a location where visibility is not restricted by buildings, walls, hedges or other obstructions, to allow pedestrians to assess gaps in traffic and not diminish a driver’s ability to stop safely if required.

There are a handful, but mostly not.

Does this one count?

How about this one?

Who’s fault is this?

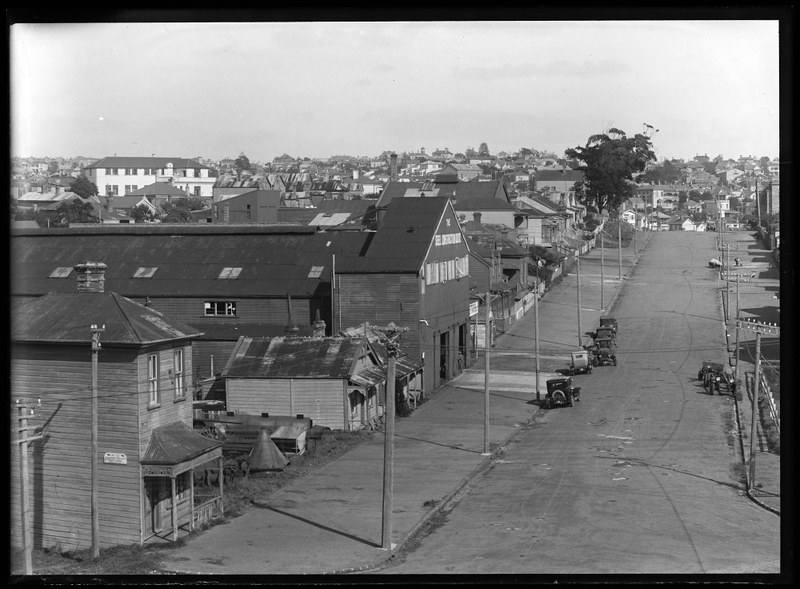

As mentioned in the last post, the current road (and footpath) layout and widths is a result of doing nothing for over 100 years. The layout is identical to that in 1908, with the exception of the motorway and the loss of some streets within the City Works Depot:

City of Auckland Map, 5 November 1919, ACC 014 Record E11, Auckland Council Archives

Vernon Street has always had narrow footpaths, though they used to at least have a consistent gradient:

23 Jan 1928 - Looking south from Drake Street (foreground) up Vernon Street, showing Freemans Hotel on right (Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries, 4-2227)

and sale Street has always been wide…

1928 - Looking south west from Wellesley Street towards Ponsonby, showing the south side of Sale Street, the premises of Steel Construction Company and some houses in Freemans Bay (Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries, 1-W278)

But keep in two things in mind:

- The driveway designs and parking designations were perpetrated against the existing environment - they are not inherent, original nor accidental

- Hobsonville Point and Long Bay were fields, but now have footpaths suitable for all users

Victoria Quarter highlights the lack of imagination and care the inner portions of Auckland City have experienced for the last 50 years.

What to do?

So, does all this indicate that this is somewhere that Auckland Council might envision as a ‘vibrant urban community’? Somewhere that they are suggesting people should give up their backyards, big houses and nice smooth footpaths for?

I suspect not.

The simplest fix will come from deciding what the area is for (already done!) - defining a hierarchy of needs based on the goals of the Auckland PlanCentre Master Plan and Auckland Council District Plan (???). The solutions will become clear once that assessment is done, if it hasn’t been done already.

So where is the plan to achieve this vision?

Next time

Next time I’ll be wrapping up with the intersection design of the area.